Stay Alfred at 80 on the Commons Columbus Reviews

| Al Smith | |

|---|---|

Smith in the 1920s | |

| 42nd Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1923 – Dec 31, 1928 | |

| Lieutenant | George R. Lunn Seymour Lowman Edwin Corning |

| Preceded by | Nathan L. Miller |

| Succeeded by | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| In office Jan 1, 1919 – December 31, 1920 | |

| Lieutenant | Harry C. Walker |

| Preceded by | Charles Southward. Whitman |

| Succeeded by | Nathan Fifty. Miller |

| 8th President of the New York City Board of Aldermen | |

| In office January 1, 1917 – December 31, 1918 | |

| Preceded past | Frank Dowling |

| Succeeded by | Robert L. Moran |

| Sheriff of New York County | |

| In office 1916–1917 | |

| Preceded past | Max Samuel Grifenhagen |

| Succeeded past | David H. Knott |

| Member of the New York Country Associates from New York County's 2nd district | |

| In office January 1, 1904 – December 31, 1915 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Bourke |

| Succeeded by | Peter J. Hamill |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Alfred Emanuel Smith (1873-12-30)December thirty, 1873 New York City, New York, U.Due south. |

| Died | October 4, 1944(1944-10-04) (aged seventy) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine Dunn (m. ; died ) |

| Children | 5 |

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October four, 1944) was an American political leader who served four terms equally Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American female parent and a Civil War-veteran Italian-American father, Smith was raised in the Lower East Side of Manhattan nearly the Brooklyn Span. He resided in that neighborhood for his entire life. Although Smith remained personally untarnished by corruption, he—like many other New York politicians—was linked to the notorious Tammany Hall political car that controlled New York City politics during his era.[1] Smith served in the New York State Assembly from 1904 to 1915 and held the position of Speaker of the Assembly in 1913. Smith also served equally sheriff of New York County from 1916 to 1917. He was offset elected governor of New York in 1918, lost his 1920 bid for re-election, and was elected governor again in 1922, 1924, and 1926. Smith was the foremost urban leader of the Efficiency Movement in the United states of america and was noted for achieving a wide range of reforms as New York governor in the 1920s.

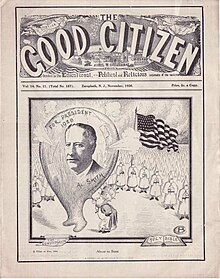

Smith was the outset Roman Catholic to exist nominated for president of the U.s. by a major party. His 1928 presidential candidacy mobilized both Catholic and anti-Cosmic voters.[2] Many Protestants (including German Lutherans and Southern Baptists) feared his candidacy, believing that the Pope in Rome would dictate his policies. Smith was also a committed "wet", which was a term used for opponents of Prohibition; as New York governor, he had repealed the state'southward prohibition law. As a "moisture", Smith attracted voters who wanted beer, wine and liquor and did not like dealing with criminal bootleggers, along with voters who were outraged that new criminal gangs had taken over the streets in most large and medium-sized cities.[3] Incumbent Republican Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover was aided by national prosperity, the absence of American involvement in war and anti-Catholic bigotry, and he defeated Smith in a landslide in 1928.

Smith sought the 1932 Democratic presidential nomination simply was defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt, his sometime marry and successor as Governor of New York. Smith so entered business in New York City, became involved in the structure and promotion of the Empire Country Building, and became an increasingly song opponent of Roosevelt'due south New Deal.

Early life [edit]

Al Smith attended St. James school through the 8th class, his simply formal education.

Smith was born at 174 South Street and raised in the Fourth Ward on the Lower Eastward Side of Manhattan; he resided there for his entire life.[4] His mother, Catherine (née Mulvihill), was the daughter of Maria Marsh and Thomas Mulvihill, who were immigrants from County Westmeath, Republic of ireland.[5] His father, baptised Joseph Alfred Smith in 1839, was the son of Emanuel Smith, an Italian marinaro.[ citation needed ] The elder Alfred Smith (Anglicized name for Alfredo Emanuele Ferraro) was the son of Italian and German[6] [7] immigrants. He served with the 11th New York Burn down Zouaves in the opening months of the Civil State of war.

Smith grew up with his family struggling financially in the Gold Age; New York City matured and completed major infrastructure projects. The Brooklyn Bridge was being constructed nearby. "The Brooklyn Bridge and I grew up together", Smith would later recall.[8] His four grandparents were Irish, German, Italian, and Anglo-Irish,[ix] but Smith identified with the Irish-American community and became its leading spokesman in the 1920s.

His father Alfred owned a small trucking firm, but died when the boy was thirteen. Aged 14, Smith had to drop out of St. James parochial school to help support the family, and worked at a fish market place for vii years. Prior to dropping out of school, he served equally an altar boy, and was strongly influenced past the Catholic priests he worked with.[x] He never attended high school or college, and claimed he learned about people by studying them at the Fulton Fish Market place, where he worked for $12 per week. His acting skills made him a success on the amateur theater circuit. He became widely known, and developed the smooth oratorical style that characterized his political career. On May 6, 1900, Al Smith married Catherine Ann Dunn, with whom he had five children.[1]

Political career [edit]

In his political career, Smith congenital on his working-class ancestry, identifying himself with immigrants and campaigning as a human being of the people. Although indebted to the Tammany Hall political machine (and particularly to its dominate, "Silent" Charlie Murphy), he remained untarnished by corruption and worked for the passage of progressive legislation.[ane] Information technology was during his early unofficial jobs with Tammany Hall that he gained renown equally an splendid speaker.[11] Smith'due south first political job was in 1895, equally an investigator in the part of the Commissioner of Jurors as appointed past Tammany Hall.

State legislature [edit]

Smith at his desk in the New York Assembly in 1913

Smith was beginning elected to the New York State Assembly (New York Co., 2d D.) in 1904, and was repeatedly elected to part, serving through 1915.[x] After being approached past Frances Perkins, an activist to ameliorate labor practices, Smith sought to amend the atmospheric condition of factory workers.

Smith served equally vice chairman of the state commission appointed to investigate manufactory conditions after 146 workers died in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. Meeting the families of the deceased Triangle factory workers left a strong impression on him. Together with Perkins and Robert F. Wagner, Smith crusaded against dangerous and unhealthy workplace conditions and championed cosmetic legislation.[eleven] [12]

The Commission, chaired by State Senator Robert F. Wagner, held a series of widely publicized investigations around the state, interviewing 222 witnesses and taking 3500 pages of testimony. They hired field agents to exercise on-site inspections of factories. Starting with the issue of fire safety, they studied broader issues of the risks of injury in the factory environment. Their findings led to thirty-eight new laws regulating labor in New York State, and gave each of them a reputation as leading progressive reformers working on behalf of the working class. In the process, they changed Tammany's reputation from mere corruption to progressive endeavors to assist the workers.[xiii] New York Metropolis's Fire Chief John Kenlon told the investigators that his section had identified more than 200 factories where conditions resulted in risk of a fire like that at the Triangle Factory.[14]

The State Commission's reports led to the modernization of the state'south labor laws, making New York State "ane of the well-nigh progressive states in terms of labor reform."[15] [16] New laws mandated better building access and egress, fireproofing requirements, the availability of burn down extinguishers, the installation of alarm systems and automatic sprinklers, better eating and toilet facilities for workers, and limited the number of hours that women and children could piece of work. In the years from 1911 to 1913, 60 of the sixty-four new laws recommended by the Committee were legislated with the back up of Governor William Sulzer.[17]

In 1911, the Democrats obtained a majority of seats in the Country Assembly, and Smith became Majority Leader and Chairman of the Committee on Ways and Ways. The following year, following the loss of the majority, he became the Minority Leader. When the Democrats reclaimed the bulk afterward the next ballot, he was elected Speaker for the 1913 session. He became Minority Leader once more in 1914 and 1915. In Nov 1915, he was elected Sheriff of New York County, New York. By at present he was a leader of the Progressive motility in New York City and state. His campaign manager and summit aide was Belle Moskowitz, a daughter of Jewish immigrants.[i]

Governor (1919–20, 1923–28) [edit]

After serving in the patronage-rich job of Sheriff of New York County, Smith was elected President of the Board of Aldermen of the Metropolis of New York in 1917. Smith was elected Governor of New York at the New York Land ballot of 1918 with the help of Irish potato and James A. Farley, who brought Smith the upstate vote.[ citation needed ]

In 1919, Smith gave the famous speech "A human as low and hateful every bit I tin movie",[18] making a drastic break with publisher William Randolph Hearst. Hearst, known for his notoriously sensationalist and largely left-wing position in the country Autonomous Political party, was the leader of its populist fly in the urban center. He had combined with Tammany Hall in electing the local administration, and had attacked Smith for starving children past not reducing the toll of milk.[xix]

Smith lost his bid for re-election in the 1920 New York gubernatorial election, but was once more elected governor in 1922, 1924 and 1926, with Farley managing his entrada. In his 1922 re-election, he embraced his position as an anti-prohibitionist. Smith offered alcohol to guests at the Executive Mansion in Albany, and repealed the state's Prohibition enforcement statute, the Mullan-Gage constabulary.[20]

As governor, Smith became known nationally as a progressive who sought to make government more efficient and more effective in meeting social needs. Smith's young assistant Robert Moses congenital the nation's first land park system and reformed the civil service, later on gaining appointment as Secretarial assistant of State of New York. During Smith's time in office, New York strengthened laws governing workers' compensation, women's pensions and children and women's labor with the help of Frances Perkins, soon to be President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Labor Secretary.

Time cover, July 13, 1925

In 1924, Smith unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for president, advancing the crusade of civil liberty by decrying lynching and racial violence. Roosevelt delivered the nominating speech for Smith at the 1924 Democratic National Convention in which he saluted Smith equally "the Happy Warrior of the political battlefield."[i] Smith represented the urban, due east declension wing of the party as an anti-prohibition "moisture" candidate, while his chief rival for the nomination, President Woodrow Wilson's son-in-law William Gibbs McAdoo, a quondam Secretary of the Treasury, stood for the more rural tradition and prohibition "dry" candidacy.[21] The party was hopelessly divide betwixt the two. An increasingly chaotic convention balloted 100 times before both men accepted that neither would be able to win the required two-thirds of the votes, and then each withdrew. On the 103rd election, the exhausted party nominated the little-known John W. Davis of W Virginia, a former congressman and United states Ambassador to Keen Britain who had been a dark horse presidential candidate in 1920. Davis lost the election by a landslide to the Republican Calvin Coolidge, who won in part considering of the prosperous times.

Undeterred, Smith returned to fight a determined campaign for the party's nomination in 1928.

1928 election [edit]

Reporter Frederick William Wile made the ofttimes-repeated observation that Smith was defeated by "the three P's: Prohibition, Prejudice and Prosperity".[22] The Republican Party was yet benefiting from an economic blast, as well equally a failure to reapportion Congress and the electoral college following the 1920 demography,[23] which had registered a 15 percent increase in the urban population. The party was biased toward small-town and rural areas. Its presidential candidate Herbert Hoover did little to alter these events.

Historians agree that prosperity, along with widespread anti-Catholic sentiment against Smith, made Hoover'south election inevitable.[24] He defeated Smith by a landslide in the 1928 election, carrying 5 Southern states in crossover voting by conservative white Democrats. (Since the disenfranchisement of blacks in the S at the turn of the century, whites had dominated voting in that region.)

The fact that Smith was Catholic and the descendant of Catholic immigrants was instrumental in his loss of the election of 1928.[ten] Historical hostilities betwixt Protestants and Catholics had been carried by national groups to the United States by immigrants, and centuries of Protestant domination allowed myths and superstitions most Catholicism to flourish. Long-established Protestants had viewed the waves of Catholic immigrants from Ireland, Italy and Eastern Europe since the mid-19th century with suspicion. In addition, many Protestants carried old fears related to extravagant claims of i religion against the other which dated back to the European wars of organized religion. They feared that Smith would answer to the Pope rather than the Usa Constitution.

White rural conservatives in the South also believed that Smith's shut association with Tammany Hall, the Autonomous automobile in Manhattan, showed that he tolerated corruption in authorities, while they overlooked their own brands of information technology. Another major controversial issue was the continuation of Prohibition, which was widely considered a problem to enforce. Smith was personally in favor of the relaxation or repeal of Prohibition laws, because they had given rise to more criminality. The Autonomous Political party separate Northward and South on the issue, with the more rural Southward continuing to favor Prohibition. During the campaign, Smith tried to duck the issue with not-committal statements.[25]

Smith was an articulate proponent of skillful government and efficiency, every bit was Hoover. Smith swept the entire Catholic vote, which had been split in 1920 and 1924 betwixt the parties; he attracted millions of Catholics, generally ethnic whites, to the polls for the showtime time, especially women, who were first allowed to vote in 1920. He lost important Democratic constituencies in the rural North too as in Southern cities and suburbs. Nevertheless, he did win votes in the Deep Southward, thanks in office to the entreatment of his running mate, Senator Joseph Robinson from Arkansas, but he lost five states in that region to Hoover. Smith carried the 10 almost populous cities in the United States, an indication of the rise ability of the urban areas and their new demographics.

Smith was not a very expert campaigner. His campaign theme song, "The Sidewalks of New York", had trivial appeal among rural folks, and they establish that his 'city' accent, when heard on radio, seemed slightly foreign. Smith narrowly lost New York State, whose electors were biased in favor of rural upstate and largely Protestant districts. However, in 1928 his fellow Democrat Roosevelt (a Protestant of Dutch old-line stock) was elected to replace him as governor of New York.[26] Farley left Smith'south campsite to run Franklin D. Roosevelt'south successful campaign for governor in 1928, and and then Roosevelt'due south successful campaigns for the Presidency in 1932 and 1936.

Voter realignment [edit]

Some political scientists believe that the 1928 election started a voter realignment that helped develop Roosevelt's New Deal coalition.[27] 1 political scientist said, "...not until 1928, with the nomination of Al Smith, a northeastern reformer, did Democrats make gains among the urban, blue-collar and Cosmic voters who were later to become cadre components of the New Deal coalition and interruption the design of minimal form polarization that had characterized the Fourth Political party System."[28] Even so, Allan Lichtman's quantitative assay suggests that the 1928 results were based largely on religion and are non a useful barometer of the voting patterns of the New Deal era.[29]

Finan (2003) says Smith is an underestimated symbol of the changing nature of American politics in the offset half of the last century. He represented the rising ambitions of urban, industrial America at a time when the hegemony of rural, agrarian America was in reject, although many states had legislatures and congressional delegations biased toward rural areas considering of lack of redistricting after censuses. Smith was continued to the hopes and aspirations of immigrants, specially Catholics and Jews from eastern and southern Europe. Smith was a devout Catholic, simply his struggles confronting religious bigotry were often misinterpreted when he fought the religiously inspired Protestant morality imposed past prohibitionists.

Opposition to Roosevelt and the New Deal [edit]

Smith felt slighted by Roosevelt during the latter's governorship. They became rivals in the 1932 Democratic Party presidential primaries afterwards Smith decided to run for the nomination against Roosevelt, the presumed favorite. At the convention, Smith's animosity toward Roosevelt was so neat that he put bated longstanding rivalries to work with McAdoo and Hearst to block FDR's nomination for several ballots. That coalition fell apart when Smith refused to work on finding a compromise candidate; instead, he maneuvered to get the nominee. Subsequently losing the nomination, Smith eventually campaigned for Roosevelt in 1932, giving a particularly important speech on behalf of the Democratic nominee at Boston on Oct 27 in which he "pulled out all the stops."[30]

Franklin D. Roosevelt (left) and Al Smith (right) in Albany, New York

Smith became highly critical of Roosevelt's New Deal policies, which he deemed a expose of good-government progressive ideals and ran counter to the goal of close cooperation with business. Smith joined the American Liberty League, an organization founded by conservative Democrats who disapproved of Roosevelt'southward New Deal measures and tried to rally public opinion against the New Bargain. The League published pamphlets and sponsored radio programs, arguing that the New Deal was destroying personal liberty. Yet, the League failed to gain support in the 1934 or 1936 elections and rapidly declined in influence. Information technology was officially dissolved in 1940.[31] [32] Smith'southward antipathy to Roosevelt and his policies was so great that he supported Republican presidential nominees Alfred Chiliad. Landon in the 1936 election and Wendell Willkie in the 1940 election.[1]

Although personal resentment was one factor in Smith'south break with Roosevelt and the New Bargain, Christopher Finan (2003) argues that Smith was consistent in his beliefs and politics—suggesting that Smith e'er believed in social mobility, economic opportunity, religious tolerance, and individualism. Despite the interruption between the men, Smith and Eleanor Roosevelt remained close. In 1936, while Smith was in Washington making a fierce radio set on on the President, she invited him to stay at the White House. To avoid embarrassing the Roosevelts, he declined. Historian Robert Slayton notes that Smith and Franklin Roosevelt did not reconcile until a brief meeting in June 1941, and he as well suggests that during the early on 1940s the antipathy which Smith held toward his former ally had waned.[33] Upon the death of Smith's wife Katie in May 1944, FDR sent Smith a note of personal condolence. Smith'due south grandchildren afterward recalled that Smith was greatly touched by it.[34]

Business organisation life and later years [edit]

After the 1928 election, Smith became the president of Empire State, Inc., the corporation that built and operated the Empire Land Edifice. Construction for the edifice symbolically began on March 17, 1930, St. Patrick's Day, per Smith'south instructions. Smith's grandchildren cut the ribbon when the world's tallest skyscraper opened on May ane, 1931, which was May 24-hour interval, an international labor celebration. Its structure had been completed in only 13 months, a record for such a large projection.

As with the Brooklyn Bridge, which Smith had seen being built from his Lower East Side adolescence domicile, the Empire State Edifice was both a vision and an achievement that had been constructed by combining the interests of all, rather than beingness divided past the interests of a few. Smith connected to promote the Empire Country Building, which was derided equally the "Empty State Building" due to a lack of tenants, in the years following its construction.[35] [36]

In 1929, Smith was awarded the Laetare Medal by the University of Notre Matriarch, considered the virtually prestigious award for American Catholics.[37]

Al Smith (correct) in December 1929 during his time as manager of Empire State, Inc.

In 1929 Smith was elected President of the Lath of Trustees of the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University.[38] Knowing his fondness for animals, in 1934 Robert Moses made Al Smith the Honorary Night Zookeeper of the newly-renovated Central Park Zoo. Though a ceremonial title, Smith was given keys to the zoo and often took guests to come across the animals subsequently hours.[39]

Smith was an early and vocal critic of the Nazi regime in Germany. He supported the Anti-Nazi cold-shoulder of 1933 and addressed a mass-meeting at Madison Square Garden against Nazism that March.[40] His speech communication was included in the 1934 album Nazism: An Assault on Civilization.[41] In 1938, Smith took to the airwaves to denounce Nazi brutality in the wake of Kristallnacht. His words were published in The New York Times article "Text of the Catholic Protest Circulate" of November 17, 1938.[42] [43]

Similar most New York City businessmen, Smith enthusiastically supported American military involvement in World War II. Although he was not asked by Roosevelt to play any role in the war endeavour, Smith was an active and vocal proponent of FDR's attempts to meliorate the Neutrality Act in club to allow "Cash and Acquit" sales of war equipment to be made to the British. Smith spoke on behalf of the policy in October 1939, to which FDR responded directly: "Very many thank you. You were grand."[44]

In 1939 Smith was appointed a Papal Chamberlain of the Sword and Greatcoat, one of the highest honors which the Papacy bestowed on a layman.

Smith died at the Rockefeller Found Hospital on October four, 1944, of a heart attack, at the age of 70. He had been broken-hearted over the expiry of his wife from cancer v months earlier, on May iv, 1944.[45] He is interred at Calvary Cemetery.[46]

Legacy [edit]

Buildings and other landmarks named after Smith include the following:

- Alfred E. Smith Building, a 1928 skyscraper in Albany, New York;

- Governor Alfred E. Smith Houses, a public housing development in Lower Manhattan near his birthplace;

- Governor Alfred E. Smith Park, a playground in the Two Bridges neighborhood in Manhattan near his birthplace;

- Governor Alfred E. Smith, a former front line and current reserve fireboat in the New York Urban center Fire Department fleet;

- Governor Alfred E. Smith Sunken Meadow State Park, a land park in the Town of Smithtown, Suffolk County;

- Alfred E. Smith Recreation Centre, a youth activity center in the Two Bridges neighborhood, Manhattan;

- PS 163 Alfred E. Smith Schoolhouse, a school on the Upper West Side of Manhattan;

- PS ane Alfred E. Smith School, a schoolhouse in Manhattan's Chinatown;

- Alfred E. Smith Career and Technical Instruction High School in the Due south Bronx;

- Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner, a fundraiser held for Catholic Charities and a finish on the presidential entrada trail;

- Smith Hall, a residence hall at Hinman Higher, Binghamton University;

- Smith Hall, a residence hall at Farmingdale State Higher; and

- Campsite Smith, a State owned military installation of the New York Regular army National Guard in Cortlandt Estate well-nigh Peekskill, NY, about 30 miles (48 km) north of New York City, at the northern edge of Westchester Canton and consists of i,900 acres (7.7 km2).

Alfred Due east. Smith Memorial at New York Medical College

The Alfred Smith School, PS 163

Alfred Eastward. Smith Career and Technical Education High School in the South Bronx

The Alfred E. Smith Building in Albany, New York

Governor Alfred E. Smith Sunken Meadow State Park in Suffolk Canton

Popular civilisation references [edit]

- Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt were filmed by Lee de Forest in his DeForest Phonofilm sound-on-moving picture procedure during the 1924 Democratic Convention, which ran from June 21 to July 9. This film is now in the Maurice Zouary collection at the Library of Congress.[47]

- In Sinclair Lewis' 1928 novel The Man Who Knew Coolidge, Smith is cited as an example of the opportunities "in this new and increasingly practical America for any bright beau today!" [48]

- In Harry Turtledove's alternate history Southern Victory series, in which the Confederate States of America wins the American Civil War in 1862, Al Smith is elected President of the United States in 1936 on the Socialist Party ticket, defeating Autonomous incumbent Herbert Hoover. As per the Richmond Understanding with Amalgamated President Jake Featherston, he immune plebiscites to exist held in the states of Kentucky, Sequoyah and Houston on re-admittance to the Confederacy; the rejection of readmittance in Sequoyah serves as a casus belli for the Second Neat State of war in North America (1941–1944). He serves until 1942, when he is killed in a bombing raid on the Powel Firm in Philadelphia and is succeeded by his Vice President Charles W. La Follette (the fictional son of Robert M. La Follette).

- Smith was portrayed by Alan Bunce in the 1960 picture show Sunrise at Campobello, and past Wilbur Fitzgerald in HBO'southward 2005 TV-movie Warm Springs. Both of these movies focus on Franklin D. Roosevelt'south struggle with polio.[49]

Electoral history [edit]

New York gubernatorial elections, 1918–1926 [edit]

| Governor candidate | Running Mate | Party | Popular Vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfred E. Smith | Harry C. Walker | Democratic | 1,009,936 | (47.37%) |

| Charles S. Whitman | Edward Schoeneck (Republican), Mamie West. Colvin (Prohibition) | Republican, Prohibition | 995,094 | (46.68%) |

| Charles Wesley Ervin | Ella Reeve Bloor | Socialist | 121,705 | (5.71%) |

| Olive One thousand. Johnson | Baronial Gillhaus | Socialist Labor | 5,183 | (0.24%) |

| Governor candidate | Running Mate | Party | Pop Vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nathan Fifty. Miller | Jeremiah Wood | Republican | 1,335,878 | (46.58%) |

| Alfred E. Smith | George R. Fitts | Democratic | 1,261,812 | (44.00%) |

| Joseph D. Cannon | Jessie Wallace Hughan | Socialist | 159,804 | (5.57%) |

| Dudley Field Malone | Farmer-Labor | 69,908 | (ii.44%) | |

| George F. Thompson | Edward 1000. Deltrich | Prohibition | 35,509 | (1.24%) |

| John P. Quinn | Socialist Labor | 5,015 | (0.17%) | |

- List of candidates, (.pdf) in The New York Times of September 13, 1920

| Governor candidate | Running Mate | Party | Popular Vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfred E. Smith | George R. Lunn | Autonomous | i,397,670 | (55.21%) |

| Nathan Fifty. Miller | William J. Donovan | Republican | 1,011,725 | (39.97%) |

| Edward F. Cassidy | Theresa B. Wiley | Socialist, Farmer-Labor | 109,119 | (iv.31%) |

| George K. Hinds | William C. Ramsdell | Prohibition | 9,499 | (0.38%) |

| Jeremiah D. Crowley | John E. DeLee | Socialist Labor | nine,499 | (0.38%) |

| Governor candidate | Running Mate | Political party | Popular Vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfred East. Smith | George R. Lunn | Democratic | i,627,111 | (49.96%) |

| Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. | Seymour Lowman | Republican | 1,518,552 | (46.63%) |

| Norman Mattoon Thomas | Charles Solomon | Socialist | 99,854 | (iii.07%) |

| James P. Cannon | Franklin P. Brill | Workers | 6,395 | (0.xx%) |

| Frank E. Passonno | Milton Weinberger | Socialist Labor | iv,931 | (0.xv%) |

| Governor candidate | Running Mate | Party | Popular Vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfred Due east. Smith | Edwin Corning | Autonomous | ane,523,813 | (52.13%) |

| Ogden 50. Mills | Seymour Lowman | Republican | ane,276,137 | (43.80%) |

| Jacob Panken | Baronial Claessens | Socialist | 83,481 | (2.87%) |

| Charles East. Manierre | Ella McCarthy | Prohibition | 21,285 | (0.73%) |

| Benjamin Gitlow | Franklin P. Brill | Workers | 5,507 | (0.19%) |

| Jeremiah D. Crowley | John E. DeLee | Socialist Labor | 3,553 | (0.12%) |

U.s.a. presidential ballot, 1928 [edit]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote | Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Per centum | Vice-presidential candidate | Dwelling house state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Herbert Hoover | Republican | California | 21,427,123 | 58.2% | 444 | Charles Curtis | Kansas | 444 |

| Alfred Due east. Smith | Democratic | New York | 15,015,464 | 40.8% | 87 | Joseph Taylor Robinson | Arkansas | 87 |

| Norman Thomas | Socialist | New York | 267,478 | 0.7% | 0 | James H. Maurer | Pennsylvania | 0 |

| William Z. Foster | Communist | Illinois | 48,551 | 0.i% | 0 | Benjamin Gitlow | New York | 0 |

| Other | 48,396 | 0.i% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 36,807,012 | 100% | 531 | 531 | ||||

| Needed to win | 266 | 266 | ||||||

- Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1928 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections . Retrieved July 28, 2005.

- Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 28, 2005.

Works [edit]

- Campaign Addresses of Governor Alfred Due east. Smith, Democratic Candidate for President 1928. Washington, DC: Autonomous National Commission, 1929.

- Progressive Democracy: Addresses & State Papers. 1928.

- Up to Now: An Autobiography (The Viking Press, 1929)

Run across also [edit]

- Alfred E. Smith Four, Smith'southward great-grandson

- Listing of covers of Time mag (1920s)

- Al Smith presidential campaign, 1928

- Al Smith presidential campaign, 1932

- J. Raymond Jones

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Slayton 2001, ch 1–iv

- ^ Neal R. Pierce, The Deep South States of America: People, Politics, and Power in the Seven States of the Deep S (1974), pp 123–61

- ^ Daniel Okrent, Last Call, 2010.

- ^ MacAdam, George (January 1920). "Governor Smith of New York". The Earth'south Work. Vol. XXXIX, no. iii. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co. p. 237. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ Slayton, Robert A. (2001). Empire Statesman: The Ascension and Redemption of Al Smith. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. xiii. ISBN978-0-684-86302-3.

- ^ Barkan, Elliott Robert (2001). Making it in America: a sourcebook on eminent ethnic Americans . Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 350. ISBN978-one-57607-098-vii.

- ^ "New York State Census, 1855; pal:/MM9.3.1/Thursday-1942-25847-12175-45 — FamilySearch.org". FamilySearch.

- ^ Slayton (2001), p. 16

- ^ Josephsons 1969

- ^ a b c Burner, David. "Al Smith". American National Biography. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Von Drehle, David (2003). Triangle: The Burn down That Changed America. New York, NY: Grove Press New York. pp. 204–210. ISBN0-8021-4151-10.

- ^ "Obama, the Triangle Fire and the Real Begetter of the New Deal". Salon.com . Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Robert Ferdinand Wagner" in Lexicon of American Biography (1977)

- ^ The New York Times: "Factory Firetraps Found by Hundreds," Oct xiv, 1911,

- ^ Richard A. Greenwald, The Triangle Burn down, the Protocols of Peace, and Industrial Democracy in Progressive Era New York (2005), 128

- ^ The Economist, "Triangle Shirtwaist: The Birth of the New Deal", March nineteen, 2011, p. 39.

- ^ Slayton, Empire Statesman (2001) pp 92–92

- ^ MacArthur, Brian (May one, 2000). The Penguin Book of 20th-Century Speeches. Penguin (Non-Classics). ISBN0-14-028500-8.

- ^ Procter, Ben H. (2007). William Randolph Hearst. Oxford University Printing The states. p. 85. ISBN978-0-19-532534-8.

- ^ Lerner, Michael (2007). Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City . Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN978-0-674-03057-2.

- ^ "Al Smitator h". Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ reprinted 1977, John A. Ryan, "Organized religion in the Election of 1928," Electric current History, December 1928; reprinted in Ryan, Questions of the Twenty-four hour period (Ayer Publishing, 1977) p.91

- ^ Prewitt, Kenneth (July 13, 2017). "The 1920 Census Broke Constitutional Norms—Let'southward Not Repeat That in 2020". Social Scientific discipline Research Council . Retrieved Dec 8, 2020.

- ^ William Eastward. Leuchtenburg, The Perils of Prosperity, 1914–32 (Chicago: Academy of Chicago, 1958) pp. 225–240.

- ^ Lichtman (1979);Slayton 2001

- ^ Slayton 2001; Lichtman (1979)

- ^ Degler (1964)

- ^ Lawrence (1996) p 34.

- ^ Lichtman (1976)

- ^ J. Joseph Huthmacher, Massachusetts People and Politics: The Transition from Republican to Democratic Dominance and Its National Implications (1973), p. 248.

- ^ George Wolfskill. The Revolt of the Conservatives: A History of the American Freedom League, 1934–1940. (Houghton Mifflin, 1962).

- ^ Jordan A. Schwarz, "Al Smith in the Thirties," New York History (1964): 316–330. in JSTOR

- ^ Slayton, Empire Statesman, pp. 397–398.

- ^ Slayton, Empire Statesman, pp. 399–400.

- ^ "NYT Travel: Empire State Building". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October xix, 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Adam (August xviii, 2008). "A Renters' Market in London". Time. Archived from the original on August nineteen, 2008. Retrieved July ten, 2010.

- ^ "Recipients". The Laetare Medal. University of Notre Matriarch. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Reznikoff, Charles, ed. 1957. Louis Marshall: Champion of Liberty. Selected Papers and Addresses. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Guild of America, p. 1123.

- ^ Caro, Robert (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. ISBN978-0-394-48076-3. OCLC 834874.

- ^ Staff. "35,000 JAM STREETS Exterior THE GARDEN; Solid Lines of Law Hard Pressed to Keep Overflow Crowds From Hall. Expanse BARRED TO TRAFFIC Mulrooney Takes Command to Avert Roughness – 3,000 at Columbus Circle Meeting. 35,000 IN STREETS OUTSIDE GARDEN", The New York Times, March 28, 1933. Accessed June 7, 2017.

- ^ Pierre van Paasen and James Waterman Wise, eds., Nazism: An Set on on Civilization (New York: Harrison Smith and Robert Haas, 1934), pp. 306–310.

- ^ David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999) ISBN 9780199743827

- ^ Slayton, Empire Statesman, p. 391.

- ^ Slayton, Empire Statesman, pp. 391–392.

- ^ "Alfred E. Smith Dies Hither at 70; 4 Times Governor — End Comes Later on a Sudden Relapse Following Earlier Turn for the Better — Ran For President in '28 — His Rise From Newsboy and Fishmonger Had No Exact Parallel in U.S. History". New York Times. October 4, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Labor – Labor Hall of Fame – Alfred E. Smith". dol.gov. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Bradley, Edwin One thousand. (June 14, 2015). The First Hollywood Sound Shorts, 1926–1931. McFarland. p. 16. ISBN9781476606842.

- ^ Lewis, Sinclair (1928). The Man who Knew Coolidge: Existence the Soul of Lowell Schmaltz, Effective and Nordic Citizen . Harcourt, Brace. pp. 269.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (September 29, 1960). "Review i – No Title:' Sunrise at Campobello' Opens at the Palace". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved Oct xviii, 2019.

- ^ "Election result", The New York Times, 31 December 1918

Further reading [edit]

- Bornet, Vaughn Davis. Labor Politics in a Democratic Republic: Moderation, Division, and Disruption in the Presidential Election of 1928 (1964) online edition

- Chiles, Robert. "Working-Course Conservationism in New York: Governor Alfred E. Smith and 'The Property of the People of the State'" Environmental History (2013) eighteen#i pp: 157–183.

- Chiles, Robert. 2018. The Revolution of '28: Al Smith, American Progressivism, and the Coming of the New Deal. Cornell University Press.

- Colburn, David R. "Governor Alfred E. Smith and the Red Scare, 1919–20," Political Scientific discipline Quarterly, vol. 88, no. three (Sept. 1973), pp. 423–444. In JSTOR.

- Craig, Douglas B. After Wilson: The Struggle for Control of the Democratic Party, 1920–1934 (1992) online edition see Chap. 6 "The Problem of Al Smith" and Chap. 8 "'Wall Street Likes Al Smith': The Ballot of 1928"

- Degler, Carl Northward. (1964). "American Political Parties and the Ascension of the City: An Interpretation". Periodical of American History. 51 (1): 41–59. doi:10.2307/1917933. JSTOR 1917933.

- Eldot, Paula (1983). Governor Alfred E. Smith: The Politician as Reformer . Garland. ISBN0-8240-4855-5.

- Finan, Christopher M. (2003). Alfred E. Smith: The Happy Warrior. Loma and Wang. ISBN0-8090-3033-0.

- Handlin, Oscar (1958). Al Smith and His America . Little, Brown.

- Hostetler, Michael J. (1998). "Gov. Al Smith Confronts the Catholic Question: The Rhetorical Legacy of the 1928 Entrada". Advice Quarterly. 46: 12–24. doi:x.1080/01463379809370081.

- Josephson, Matthew and Hannah (1969). Al Smith: Hero of the Cities . Houghton Mifflin.

- Lawrence, David G. (1996). The Collapse of the Democratic Presidential Majority: Realignment, Dealignment, and Electoral Change from Franklin Roosevelt to Nib Clinton. Westview Press. ISBN0-8133-8984-4.

- Lichtman, Allan J. (1979). Prejudice and the old politics: The Presidential ballot of 1928 . Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN0-8078-1358-3. OCLC 4492475.

- Lichtman, Allan (1976). "Critical Election Theory and the Reality of American Presidential Politics, 1916–forty". The American Historical Review. 81 (two): 317–351. doi:10.2307/1851173. JSTOR 1851173.

- Carter, Paul A. (1980). "Deja Vu; Or, Dorsum to the Drawing Board with Alfred E. Smith". Reviews in American History. eight (2): 272–276. doi:ten.2307/2701129. JSTOR 2701129. ; review of Lichtman

- Moore, Edmund A. (1956). A Catholic Runs for President: The Campaign of 1928. OCLC 475746. online edition

- Neal, Donn C. (1983). The Earth beyond the Hudson: Alfred E. Smith and National Politics, 1918–1928. New York: Garland. p. 308. ISBN978-0-8240-5658-2.

- Neal, Donn C. (1984). "What If Al Smith Had Been Elected?". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 14 (2): 242–248.

- Perry, Elisabeth Israels (1987). Belle Moskowitz: Feminine Politics and the Exercise of Power in the Age of Alfred Eastward. Smith. Oxford Academy Press. p. 280. ISBN0-19-504426-half-dozen.

- "Smith to Talk October. 23". New York Times. 1940. p. 17.

- "Smith Says Roosevelt Angry Spirit of Class Hatred in Nation". New York Times. 1940. pp. i, 18.

- Rulli, Daniel F. "Candidature in 1928: Chickens in Pots and Cars in Backyards," Didactics History: A Journal of Methods, Vol. 31#1 pp 42+ (2006) online version with lesson plans for class

- Schwarz, Jordan A. "Al Smith in the Thirties." New York History (1964): 316–330. in JSTOR

- Slayton, Robert A. (2001). Empire Statesman: The Rising and Redemption of Al Smith. Free Press. p. 480. ISBN978-0-684-86302-3. , the standard scholarly biography

- Stonecash, Jeffrey M., et al. "Politics, Alfred Smith, and Increasing the Power of the New York Governor's Office." New York History (2004): 149–179. in JSTOR

- Sweeney, James R. "Rum, Romanism, and Virginia Democrats: The Party Leaders and the Campaign of 1928." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 90 (Oct 1982): 403–31.

External links [edit]

- Alfred E. Smith at Find a Grave

- "Alfred E. Smith Dies Hither at 70; 4 Times Governor". The New York Times. October 4, 1944.

- "Happy Warrior Playground". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

- "Governor Alfred Eastward. Smith Park". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

- "Al Smith". Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site.

- Murphy, Kevin C. "Lost Warrior: Al Smith and the Fall of Tammany".

- A film clip "Al Smith Hails Stop of Dry Police, 1933/xi/13 (1933)" is available at the Net Archive

- Booknotes interview with Robert Slayton on Empire Statesman: The Rise and Redemption of Al Smith, May 13, 2001.

- "Al Smith, Presidential Contender" from C-SPAN's The Contenders

- Finding aid for the Alfred E. Smith Papers at the Museum of the Urban center of New York

- Alfred E. Smith – The People's Politician? from the Museum of the City of New York Collections blog

- Newspaper clippings well-nigh Al Smith in the 20th Century Press Athenaeum of the ZBW

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al_Smith

Publicar un comentario for "Stay Alfred at 80 on the Commons Columbus Reviews"